*Photo credits: Heather Cohen

A homesteader’s work in the garden is never done. In spring, we plan our space and plant our seeds. We nurture our fragile seedlings, providing them with healthy soil, clean water, and warming sun. When summer’s heat begins to beat down, we prune, trellis, and irrigate our precious plants. We weed and water and weed again in what seems like an eternal, uphill battle against grasses, plantains, and pigweeds.

As fall arrives, baskets and bushels of colorful produce fill our kitchens as we begin to reap the bounty of our labor, harvesting, feasting, and preserving the garden’s abundance in preparation for the winter months ahead. Then, during winter, we plan and dream, fantasizing about the staggering array of diversity offered within the vividly colored pages of our favorite seed catalogs.

With every season there comes a task, but perhaps no job is more important than that of the seed saver, who carries the spirit of our gardens from the harvest in the fall, through the dormant winter months and into the next spring to once again be planted in the embrace of the earth’s warm soil. Without the seed saver, the cycle could not reliably continue.

Saving seeds is not just pragmatic, it is critical to preserving the heritage, cultures, and histories of all who have stewarded these precious crops before us. Without seeds, we would have no food, and early farmers understood that by selecting seeds from the biggest and best-producing plants in their fields, the yield of their harvests and the quality of their produce would continue to improve. These early farmers were the first plant breeders, and because of their efforts, we’re blessed with an incredible bounty of fruits and vegetables today, with colors and flavors that delight the senses and enchant the imaginations of culinary artisans.

Preserving Our Past and Our Future

As seed savers, we do our part to preserve the work of these first farmers, honoring their time and dedication. Within each seed saved is the story of every gardener who grew that cultivar before. Just as we care for these crops, fulfilling their needs in order to sustain their life, they in turn provide us with the nourishment we need to sustain ours. This reciprocal relationship doesn’t end with the harvest; it carries on, through the seed, into the next season.

This commitment is not to be taken lightly. Our follow-through is so critical, in fact, that to fall short of our responsibility is to endanger our very survival on this earth. The same holds true for the plants in our care. Entering into this agreement—known to botanists as “domestication”— these unique plants gave of themselves to provide us with their life-giving fruits and foliage. Through each passing season, as we selected the traits that were most valuable to us, these plants provided. But as we asked them for larger fruits, sweeter flavors, and more abundant leaves, other qualities—perhaps qualities that we may have viewed as less important—were altered and eventually lost.

Over time, these plants were changed from their wild selves to something new and different. It’s because of this exchange that many of today’s garden crops so strongly rely upon our care and attention: They’re far altered from their original wild forms and are unable to survive and thrive as they once could without the pruning, weeding, and irrigation that we’ve agreed to provide.

The same can be said of our own species. Taking part in this sacred exchange has also changed us forever. Sometime around 12,000 years ago, many of our ancestors began to shift away from their nomadic, hunter-gatherer behavior into a more settled, agrarian lifestyle. They began this shift by first learning to manage the wild places where their food plants already grew; they gave them space and urged them to thrive. Eventually, people began to coax these plants out of their habitats, observing their behaviors and selecting from the strongest and most productive species.

Nowadays, many of us no longer roam to follow the seasons, the migrating animals, and a ready supply of food, and instead live in constructed cities and towns. Just as these plants have allowed themselves to grow fully dependent upon our care, we also depend upon them. It’s only through cooperative cultivation that we’re able to prosper. Understanding the entwined nature of our relationship is paramount to success. Through seed-saving, we preserve the past while preparing for the future.

How to Save Seeds At Home

Open-Pollinated Vs. Hybrid Seeds

While modern plant breeding may appear to be limited to the realm of the scientist, small-scale farmers and backyard gardeners everywhere are still using the traditional techniques utilized by the earliest agrarians. This is only possible because of the heirloom, heritage cultivars being grown and saved in these small plots, known as “open-pollinated” (OP) cultivars. Generally speaking, this term refers to plants pollinated naturally by birds, insects, wind, or human hands.

To put it simply, seeds harvested from OP cultivars can be planted the following season and will come back “true-to-type,” meaning similar to the maternal plant. The gardener may need to take some additional precautions to avoid any cross-pollination with some plants, but the main point to understand here is that seeds saved from open-pollinated (OP) cultivars can be grown again the next year with reasonable predictability.

Conversely, many modern cultivars available today are hybrids. A hybrid is produced when two plants of the same species are cross-pollinated to produce a new cultivar. This new cultivar is referred to as the “F1 hybrid.” A common misconception is that hybrid seeds are the same as genetically-modified (GMO) seeds. This is not the case, as hybrids can be cross-pollinated by hand by a home gardener, and some can even cross-pollinate in nature. That being said, while hybrids do offer a number of benefits—such as more resilient cultivars—the seeds collected from hybrid plants aren’t likely to grow true-to-type, and therefore aren’t ideal for the beginning seed saver. All of this to say, if you’re just getting started with seed-saving, stick to saving open-pollinated seeds.

Despite the slight learning curve that can come with familiarizing yourself with the different types of seeds and plants, saving seeds from your garden is relatively straightforward and can be accomplished by anyone with a bit of patience and practice. Remember, the first seed savers weren’t scientists or academic scholars, but they did take the time to observe and develop relationships with the plants in their care, the same plants that cared for them in return with nourishing fruits, flowers, and foliage.

Seed-Saving Best Practices

Saving one’s own garden seeds can be an easy and rewarding practice for gardeners of all skill levels. Get started saving your seeds with these tips:

Start small. Begin by saving seeds from only one or two crops. Try something that you already grow in your garden, or that you enjoy eating.

Save seeds from open-pollinated (OP) cultivars. These cultivars are more likely to grow true-to-type.

The easiest garden crops to save seeds from are self-pollinating annuals. These species will produce flowers, fruits, and seeds all in one season, and are least likely to cross-pollinate with other cultivars. Some great examples include beans, peas, lettuce, and tomatoes.

Seeds are mature and ready to be harvested when the fruits are ripe. Peppers, tomatoes, and other nightshades will change color to signal their ripeness, while crops such as beans and peas will grow dry and brittle. Cantaloupes and watermelons are ripe when we eat them, which is also the perfect time to collect their seeds.

Dry seeds like beans, lettuce, and many herbs are processed by threshing and winnowing to separate the seeds from the chaff. Wet seeds need to be extracted from ripe fruits and then thoroughly rinsed before drying.

Clean your seeds well before storing them away for next season. Seeds should also be dried well before storing to avoid any mold from forming.

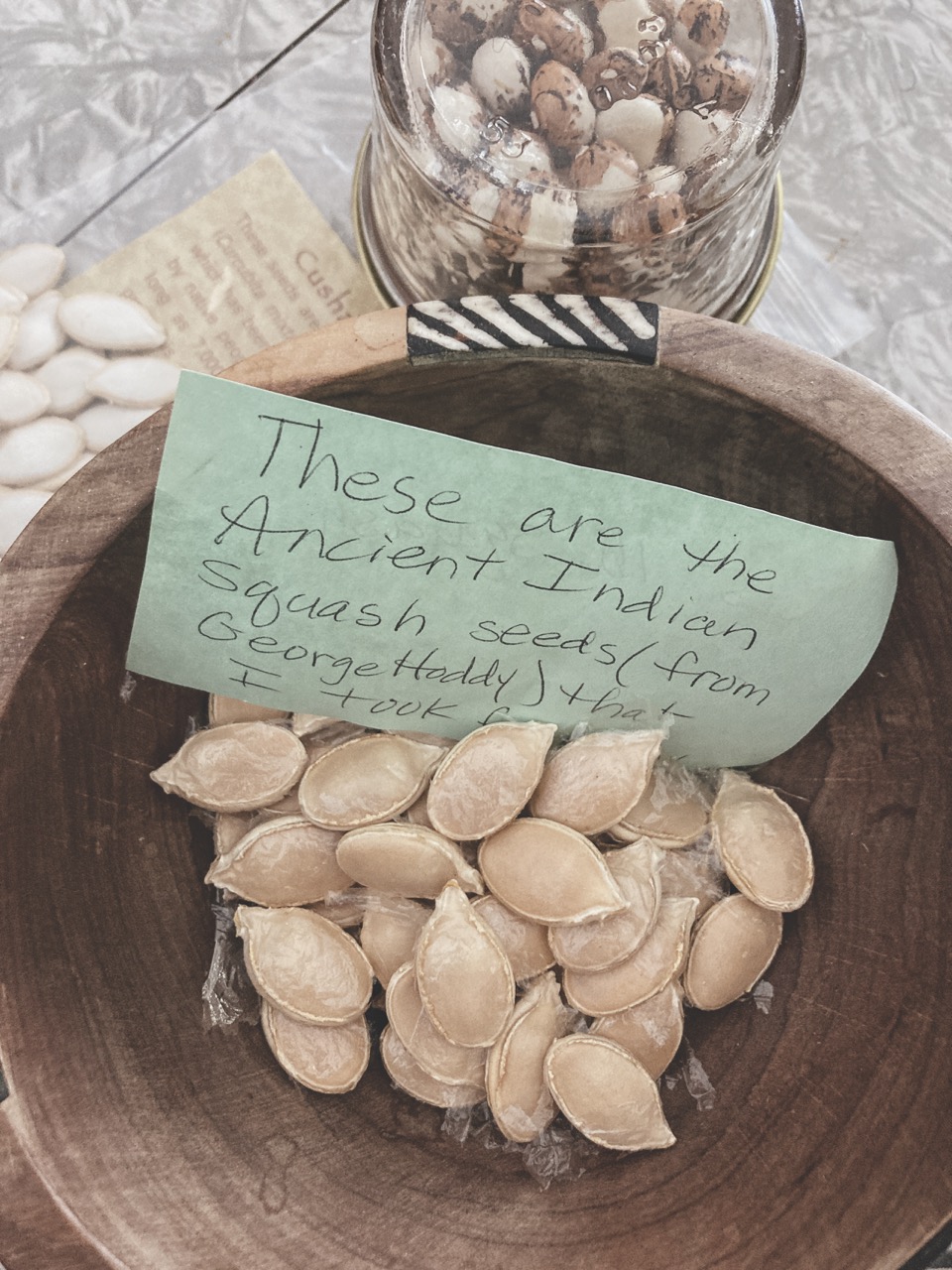

Properly label your seeds with the cultivar name, scientific name, and date of harvest.

Seeds store best when kept in a cool, dark, and dry environment. Glass jars are ideal for seed storage, but small envelopes or similar containers also work well.

For long-term storage, keep your seeds in airtight containers in a freezer. When you’re ready to grow them, let your seeds reach room temperature before opening the containers to avoid getting your seeds wet through condensation.

Above all else, have fun! Saving seeds is an important task, but also an enjoyable one. Over time you may even create your own strain of family heirloom seeds! If you’re interested in learning more, I encourage you to check out my book, Saving Our Seeds: The Practice & Philosophy.

Leave a Reply